Typography plays a central role in the design, branding, and overall readability of content. On the web, typography is achieved chiefly via webfonts. While the default system/”web-safe” fonts (hello Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif) are a reasonable and incredibly performant strategy for presenting content online, webfonts allow you to customize your typography to create a memorable, and delightful experience for your users. Even so, custom webfonts (as most nice things do) come at a performance cost. The text (and many other styles defined in your style sheet) is blocked from rendering until your requested webfont loads. This means a terrible overall experience for users who may experience jank via layout repaints or worse, be presented with no text at all. Considering that webfonts are responsible for the design and general readability of your web content, optimizing your web fonts should be of high priority in your overall performance strategy.

Flashy in a bad way

There are 2 kinds of problems that can arise when using webfonts; Flash of invisible text (FOIT) and Flash of Unstyled Text (FOUT). FOIT is the default browser behavior to render text invisible (for about 3s) when the web font is still loading. FOUT is default behavior that renders text with the fallback system font while the web font is loading, and often occurs after FOIT timeout (~3s) has passed. If we were to compare them, FOUT is of course the lesser of the two evils; we’d rather have unstyled text than no text at all. For more on FOUT and FOIT, check out this excellent talk by Bram Stein.

Web fonts, how do they load?

In order to understand how to make our sites load webfonts better, we first have to understand how webfonts are loaded in the first place. Let’s begin by looking at the worst case scenario for loading webfonts onto a page; FOIT.

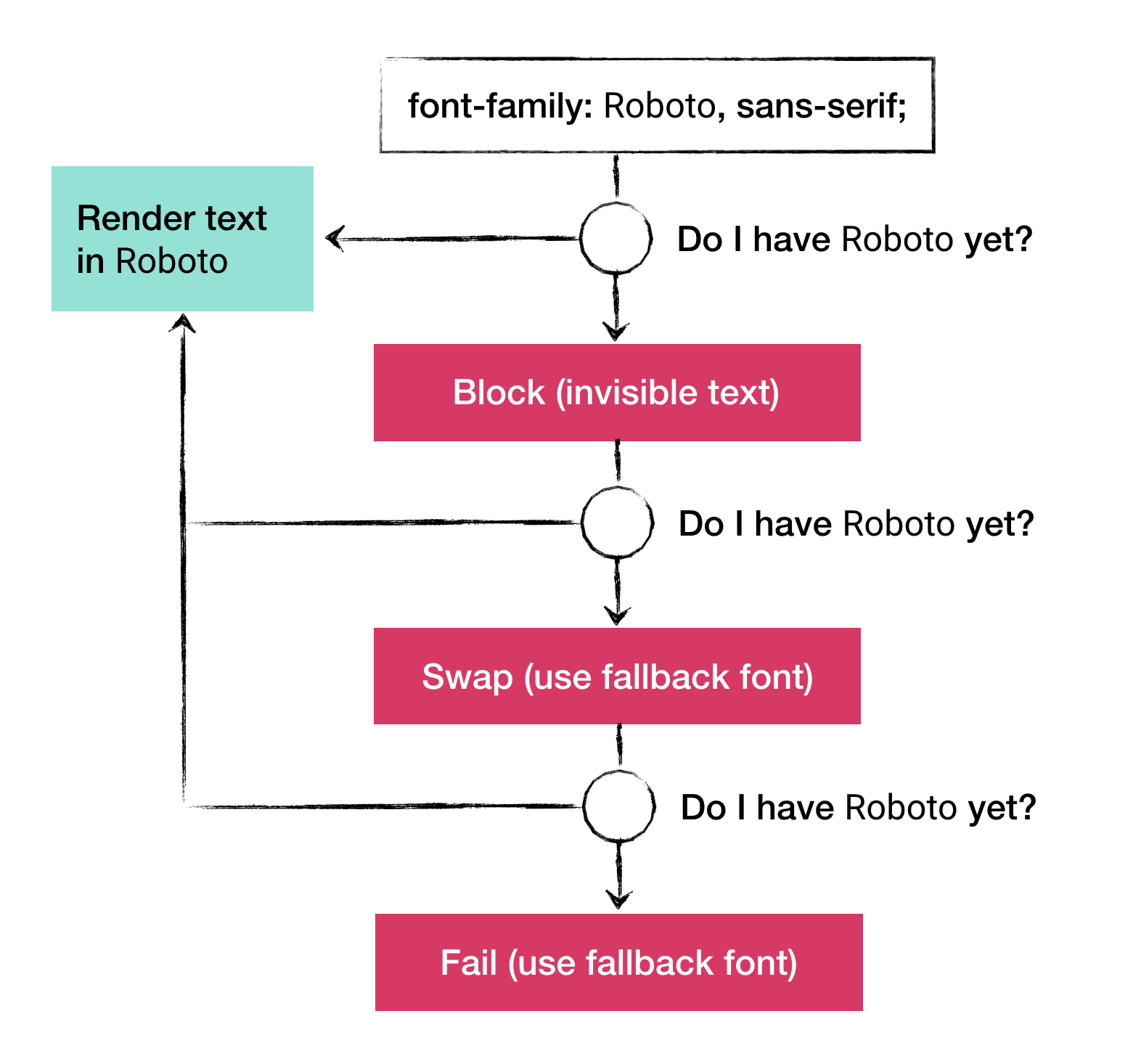

When a browser encounters a webpage, it parses the html document and subsequent stylesheets to build out a render tree, which it uses to figure out what resources it needs to render content onto the page. With this information, the browser can then begin laying out and painting the page appropriately. On encountering a webfont (the browser only does the actual download of the font when its used), the browser blocks all rendering in order to fetch the requested font, if its not yet available. This render blocking state translates to blank text from a user’s perspective (FOIT). If the font fails to load within the browser defined timeout (~3s), the text will swap out the invisible text with a fallback font (FOUT) until the requested font loads. When the long awaited for webfont finally loads, the browser then does another swap to render the proper font. For a better visual representation of this process of loading webfonts, check out Monica Dinculescu’s very useful diagram below.

Fix It

Now that we’ve established how terrible webfonts can be from a performance perspective, let’s examine some strategies to making your webfonts work a little better.

Preload is your friend, but not like your best friend. Web fonts don’t start downloading until the browser actually sees that they’re being actively used in the page content. At this point in the loading process as we saw earlier, content is already being rendered onto the screen, so the user sees blank text ☠️ . In order to save ourselves from this situation, we can tell the browser to preload fonts ahead of time so fonts are readily available right when we need them. Here’s a snippet of what that looks like courtesy of this post by Ilya Grigorik:

<head>

...

<link rel="preload" href="/fonts/awesome-l.woff2" as="font" />

</head>

@font-face { font-family: 'Awesome Font'; font-style: normal; font-weight: 400;

src: local('Awesome Font'), url('/fonts/awesome-l.woff2') format('woff2'), /*

will be preloaded */ url('/fonts/awesome-l.woff') format('woff'),

url('/fonts/awesome-l.ttf') format('truetype'), url('/fonts/awesome-l.eot')

format('embedded-opentype'); unicode-range: U+000-5FF; /* Latin glyphs */

Preloading a webfont is useful because it forces the browser to prioritize the request for a specific webfont. However, as you probably may have guessed preloading in excess can significantly worsen performance, since preloads block initial render. Instead of pre-loading the kitchen sink of webfonts, try limiting your prerenders to the most critical webfonts on the page. Another caveat to using webfonts is that its not yet fully supported by browsers.

Font-display

font-display is one of the newer css attributes that was introduced to browsers that allows you to control how the browser blocks and swaps text during the render cycle. With the new font-display attribute, you can control the length of the block and swap period (see Monica’s diagram above) with the following values, block, swap, fallback and optional. Block gives the font face a short block period and an infinite swap period, swap gives the font face a 0s block period and an infinite swap period, fallback gives the font face an extremely small block period and a short swap period and lastly optional gives the font face an extremely small block period and a 0s swap period. For more on font-display, read Monica’s demo explainer on it here.

@font-face {

font-family: "my-awesome-font";

font-display: optional; /* tells the browser to do its thing w/o forcing its hand */

src: url(my-awesome-font.woff2) format("woff2");

}

Small webfonts files

Fonts often come in various file formats so browsers can use the ones that work the best for them. There’s WOFF2, WOFF, EOT, and TTF. Of all the formats available WOFF2 is the smallest boasting ~30% file-size reduction and is therefore the optimal web format to use—assuming browser support is not your biggest concern. A further optimization you can make to help reduce your font file size is by omitting glyphs that you aren’t using from the file download. You can do this via unicode-range-subsetting to split large fonts into smaller sets and the unicode-range-setting to pick specific characters from a fontset. Glyphhanger by the Filament Group is an incredibly useful tool to get started with subsetting webfonts. Karolina Szczur also wrote extensively about this method and more in a very relevant post on the state of the web.

JavaScript to the rescue—for now.

Web fonts are primarily CSS oriented. It can therefore feel like bad practice to reach for JavaScript to solve a CSS issue, especially since JavaScript is a culprit for an ever increasing page weight. Current CSS solutions like the ones discussed earlier give developers a lot of control over font loading and rendering, but still fall short when it comes to (some) browser support and adapting to user preferences. For one, the Font Loading API provides us with an interface to define and manipulate CSS font faces and override default behavior. This gives us fine-grained control over what the user sees prior to a web font loading.

const font = new fontFace("My Awesome Font", "url(/fonts/my-awesome-font.woff2)" format('woff2')")

font.load().then (() => {

document.fonts.add(font);

document.body.style.fontFamily = "My Awesome Font, serif";

// we can also control visibility of the page based on a font loading //

var content = document.getElementById("content");

content.style.visibility = "visible";

})

Oftentimes, when we request a font, we request more than one font file; one for each style (bold, italic etc). Each font file has to load separately and can add time to the overall render cycle, thereby slowing down the page load. In cases like these, JS comes in handy because we can batch our font loads into one, and thereby fine tune how the browser handles a reflow/repaint.

Use your font and read it too.

Deciding to use webfonts on a page doesn’t always have to be a compromise between performance and design. When optimized well, webfonts can deliver a better, more delightful user experience while also maintaining a small performance footprint (is this a thing?). I’m by no means the expert on webfonts but hopefully this post and many others I referred to will help set you on the path to using webfonts more effectively for more performant websites.